Two things can be true at once.

Are public research universities broke or are they flush with cash and spending like drunken sailors? Both.

Austerity in the Mountains

The news about West Virginia University’s (WVU) plans to slash degree programs and faculty jobs understandably has captured the attention of those of us who closely follow the machinations of higher education in the United States. Inside Higher Education reports WVU’s retrenchment proposal would cut 7% of all majors at the university and eliminate 9% of all faculty positions, including tenure track positions. As someone who studies how universities operate, I can’t think of another recent re-institution plan at a major public university with the breadth of WVU’s administration proposal. WVU University is also acting fast. Word of the cuts first came in May, and the Provost’s Office, which is leading the processes, says the Board of Governors will vote on the final cuts on September 15. By major university standards, this is lightning fast.

WVU is downsizing because it faces a stark operational reality. The 2022 State Higher Education Finance (SHEF) Report indicates that 2021 public postsecondary enrollments were down over 25% from 2012. While state funding has recovered from the deep cuts experienced during the Great Recession in 2008, per-student funding is down by nearly 10% in real terms over the past 20 years. West Virginia is one of several states with a shrinking number of high school graduates, and within the state, fewer high school students are choosing to go to college. The pressure on West Virginia’s flagship (I have abandoned my campaign to erase the term flagship from our vernacular) is real. It is a different question whether it requires the extent and haste of cuts that the university appears to be undertaking. I don’t have a definitive answer, but I would be skeptical of anyone who says “yes” without proving it. Either way, the university faces real challenges that do, or at least will, require some organizational reckoning. When veteran public university leader Gordon Gee took over at WVU in 2014, he promised to boost enrollment and boost the university’s market position. That didn’t happen. Just after initiating the massive retrenchment product now underway, Gee announced that he’d retire from the presidency and take up residence as a professor of Law. An ignominious swan song, if you ask me.

Irrational exuberance in the flagships.

As the details of WVU’s's draconian retrenchment plan circulated, the Wall Street Journal reported that many other public flagship universities were burning through massive amounts of cash on what seemed to the journals (and their take was reasonable) vanity projects. It’s not that these public universities were getting better support from their states than WVU. State appropriations were, on average, down. But tuition revenue at many public flagship universities is up, way up. That’s because at many flagships, enrollment is up, but mainly because net tuition revenue is up even more.

So, many flagship universities are enrolling more students and collecting more revenue per student they enroll. In the aggregate, at many major public universities, this pattern of bringing in more students and charging each student more has made up for lagging per-student state support and led to a quicker expansion of per-student income. Tuition dependence is a bad thing for the operations of most public colleges and universities, which struggle to enroll enough students and or change enough tuition per student to maintain and expand high-quality offerings. In Unequal Higher Education, Barrett Taylor and I called tuition dependence a “distress signal” for the majority of public universities. But we also observed that a smaller number of public universities ostensibly thrive on a tuition economy model. These campuses, we argued, “developed a taste for tuition” and for the things tuition cash can buy.

A relatively few public universities - such as those highlighted by the Wall Street Journal, tuition dependence and the enrollment economy brought about a guided age. Initially cajoled into market-like behavior by policymakers who wanted universities to operate more like business and buoyed by the spigot of cash made possible by federal student loans, the public universities with national or at least regional market power leaned into the enrollment economy and reaped the riches. These campuses lure enrollments away from regional universities, non-selective private universities, and community colleges. They grew per-student revenue much faster than previous generations when they relied more on direct state funds and less on tuition fees. These places grow for the sake of growing.

Inequality in a winner-take-all enrolment economy.

Like other gilded ages, there is lots of money sloshing about, but it’s not spread around. Most public universities don’t have power in the enrollment economy. They can neither dramatically expand enrollments nor markedly increase net tuition income per student in real terms. They face exposure to anemic public investment.

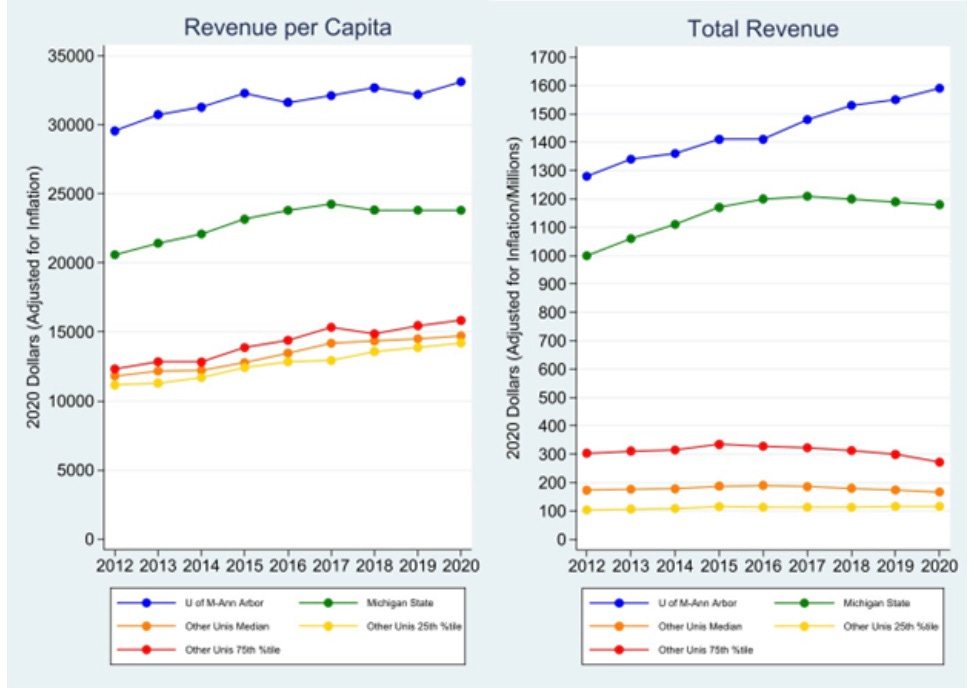

The result is growing inequality among public universities. With colleagues, I recently documented this pattern as it has played out in Michigan. Look at the gap between total revenue per student at the University of Michigan with everyone else, and then the gap again between Michigan State and the regional public universities in the state. Growing inequality.

While WVU is a “flagship” campus, a term that I’ve argued can be misleading, is on the losing side of the tuition-fueled bonanza. Simply put, WVU’s academic operations sought to reflect its flagship status, but it is a loser in the enrollment economy. West Virginia is simply not a very good place to be a flagship university. The state is not especially generous in terms of direct funding, in-state, there are relatively few students and high levels of financial need, and out-of-state students are not clamoring to attend. WVU does attract out-of-state students. About half of all undergraduates are from beyond West Virginia. Growing up in neighboring Maryland in the 1990s, I knew a few students who went to WVU out of state. The students I knew often chose to attend WVU over Frostburg or Salisbury State universities, regional public campuses on the western and eastern flanks of Maryland families generally saw as equivalent options to WVU. And the late 1990s was a lifetime ago in higher education finance terms. Since then, competition in the enrollment economy has dramatically intensified. WVU is a destination for out-of-state students. It just hasn’t pulled enough students to the state, given WV’s population slide and limited the demand for higher education among those in the state.

WVU is an enrollment economy loser. And now one of the poorest states in the country with among the greatest need for the sort of common good contributions made by a vibrant public research university has a listing flagship that’s taking on water.

Winner-take-all is replacing the common good with ambition.

When public universities that are flush with enrollment economy cash spend their money, many of their decisions are defensible because they plausibly contribute to the university’s mission. A new state-of-the-art building for STEM education is squarely within the mission. Supporting the research operation beyond the grants faculty win is also often defensible. Buying a campus in Italy to host study abroad programs might raise some eyebrows, but it is also pretty easy to argue how this is a mission-responsive move. It is true that some of this is prestige seeking, but like it or not, prestige seeking (within reason) is consistent with the university mission if campus officials seek to become more prestigious by, for example, performing more research.

Other deals and splurges are less clearly linked to the university mission but make some sense. Examples include renovated student gyms and fitness centers, new (sometimes fancy) dormitories, and subsidies for intramural sports. None of these activities are core to the public university mission, but they often are important to important stakeholders such as prospective students, alumni, and donors. It can be hard for university leaders to resist spending on the activities mentioned above because they are obliged to attract students who pay tuition and are under pressure to respond to donor preferences.

Other examples of campus spending include speculative and risky moves like investing in spin-off companies, providing excessive pay, and perks for campus leaders, such as chartering flights for the president are not easily explained as legitimate expenses. Most of these expenses, while maybe gross-looking, are fairly contained and containable. There are exceptions. Some public-private partnership deals can leave campuses with ballooning future liabilities. I would am especially concerned about university real estate speculation.

Even if many of the spending projects campuses enjoying the gilded age of tuition income undertake are individually defensible, collectively, they point to a troubling reality: higher education is increasingly a winner-take-all enterprise. The winner/loser dichotomy is experienced among individuals, between groups and between, and between institutions. Within academic departments, faculty who are able to win the right grants or consistently publish in the right journals can see their salaries increase. They can get external offers and leverage wages and preferred working conditions. They can secure consulting contracts.

Meanwhile, other faculty, even those with the protection of tenure, can see their real wages eroded by inflation because they rarely get meaningful pay adjustments. These faculty are not usually the detached permanent vacationers that are stereotypically imagined. They are often teaching large enrollment classes and doing lots of local service. Because the winners take all the good stuff. Administrative careers are also defined by winter take-all ambition to hit the jackpot of a very senior campus job. I recently wrote about how presidential salaries are so out of line with other higher education jobs that they create distorted incentives. Winning a president’s job is like hitting the jackpot.

The same winter takes all logic operations between institutions. Within institutions, ambitious faculty and administrators hope to make a name for themselves to get the next, better opportunity. For administrators, that almost always means growing things. And growing things is expensive. No one gets to be the dean by saying they want to sustainably maintain the status quo. No provost becomes a president by making sure faculty labor is distributed and compensated equitably.

Academic ambition is nothing new, but the enrollment economy has supercharged the winner-take-all aspects of life. The few public universities that have been able to not only replace lost state funding with tuition but also jump to a steeper revenue growth curve are the winners. They also provide spectacular individual career opportunities for a few individual winners who can use all that cash to grow splashy things and make a name for themselves and move on to another bigger, better job.

I see the culture of winner-take-all rewards in higher education careers and the winner-take-all competition between universities in the enrollment economy as reciprocal. As a result, even when universities do things that are plausibly consistent with their traditional missions of education, research, and public service, the motivation is often individual or institutional ambition rather than serving the common good.

Ok, enough.