I've changed my mind about university governance in Michigan

While things might look bad, the alternative is much worse. And while we are at it, stop using principal-agent theory to conceptualize higher education governance.

Michigan’s public universities enjoy constitutional autonomy. When Larry Nassar’s horrific crimes were exposed at Michigan State University (MSU, my employer), members of the university community, especially the public, demanded accountability. For many, there has never been enough accountability at MSU for what happened. One reason the level of accountability has been less than satisfying for many is that MSU has something called constitutional autonomy. Michigan’s constitution explicitly puts an arm’s length between the state government and public universities. This means that universities operate independently from the state on most matters, which limits the ability of the state’s governor to interfere with university business. In the case of MSU, the University of Michigan, and Wayne State University, institutional governance boards are elected directly by the people, which further limits the influence of the executive and legislative branches over the universities. You can read a short explainer from a few years back here.

Constitutional autonomy is no panacea. Without state coordination, there is not much to prevent Michigan’s universities from competing directly in ways that can be unproductive and inefficient. Program duplication? You betcha. Missed opportunity for shared services? Oh-ya. Less than wise elected boards ……

And, of course, there is the question of limited accountability. The fact of the matter is that Michigan’s public universities are less accountable to the governor than in other states where governance is more centralized, and the executive branch has greater authority to steer the sector. I think it is fair to say that it’s plausible that some of the dysfunction and organizational failure observed at MSU, Michigan, and Wayne over the past several years is partially attributed to this highly decentralized governance structure. It’s a more complicated question, but public universities are tuition-dependent and expensive in MI relative to many other states. That might also have something to do with the way the system is organized, or not organized, as the case may be.

But the recent past has also shown a substantial upside to Michgian’s constitutional autonomy. The upside is the alternative. Republican lead states nationwide are reaching into higher education operations to weaken tenure protections, squash diversity and inclusion programs, censor speech paradoxically under the manta of free speech, and capture control of university management and governance to align higher education with partisan priorities. Ron DeSantis is the leader in this effort, which is also happening in Texas, Missouri, and other states. I’m not linking to anything here because I bet you know all about it if you don’t Google away.

But I am writing about this today because of an extremely disturbing exchange I saw on Twitter over my morning coffee.

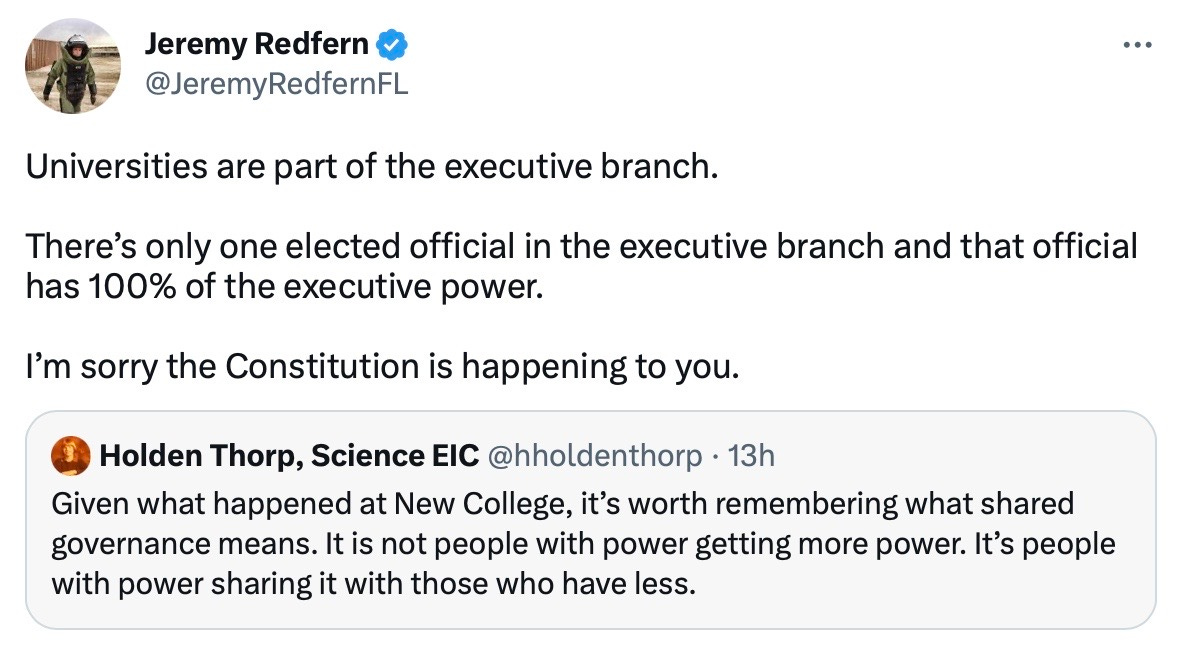

Holden Thorp, Editor-in-Chief of Science and a former university chancellor, observed correctly that the DeSantis administration was using its former powers to squash shared governance and steamroll the academic community at New College in Florida. DeSantis’ Deputy Press Secretary Jeremy Redfern quite tweeted in rely on that the constitution gives Ron the power, so suck an egg. Or, as he put it, “I am sorry that the Constitution is happening to you.”

The brazen authoritarianism is terrifying, Redfern, who we can only assume based on his job speaks for the Governor and presidential hopeful, is in no way ambiguous. The Governor will use his power to crush the independent voices in the state (and presumably the country if he were to become President). Redfern says directly: we are gonna do authoritarianism, and we are going to do it to you because we can.

This brings me back to Michigan. It would be much harder for the Michigan Governor to invade public universities through an authoritarian hostile takeover. To do so directly would require a change in the constitution. Perhaps a playable state supreme court and budget handsome could get some of it done indirectly, but that would be much more difficult to pull off and unlikely to have the same consequences even if it could be done.

Put me on team constitutional autonomy, even if it means less accountability for universities to do the things I want them to do.

And now a note to my higher education scholar colleagues.

Please stop using principle agent theory to conceptualize higher education governance because when you do, just like Redfern, you essentially assume higher education belongs to the executive branch. Higher education has many principles. Among them are students and families, academic disciplines, faculty, staff, labor unions, and the state and federal government. Thorp observes that a university is 1,000s people, not just one principal executive. I agree. But I would go even further. The university has many legitimate claimants within and outside of the organizational boundaries, including the professions. The APA and the AMA standards make legitimate claims about the university. Less directly, peer review, for example, in the form of external tenure evaluations, is a process that empowers the indirect authority of the profession over the university. Our theories matter because they guide the questions we ask, the way we design our empirical studies and the way we talk about higher education, including to advocacy groups and policymakers. Let’s start to think beyond principal-agent models.

Ok, enough.