Demise of the Cow College?

What stagnant agriculture research says about US higher education.

Agricultural research is stagnant at US colleges and universities. The federal government does not invest in ag research as it does in other areas of biological science. And within higher education, agriculture research is considered less prestigious than research in other fields. As a result, universities that specialize in agricultural research are not generally among the most prestigious and best funded institutions in the country. The status of ag research and ag colleges in US higher education is indicative of the way social preferences for particular types of research (and research funding) shapes the way universities are stratified in the country but also has implications for how pressing challenges like food security are prioritized (or not) by academic science.

Morning waffles

I delayed making Sunday morning waffles for our kids as long as I could, but by around 8:15, there was no more putting it off. Mixing the batter, I flipped on the Sony analog radio I’ve kept in my kitchen since graduate school and tuned into NRP’s Weekend Edition. One of the first stories that played as I tried to remember the waffle recipe (how many eggs?) was about agriculture research funding. Ag research funding has stagnated, and that’s bad, the reporter explained, because we need to increase crop yields and resistance to deal with a growing population and climate change. The story is linked below.

Agricultural research funding has dropped, impacting the fight against climate change

Of curse, as soon as I plated the crisped batter, making sure to give child #1 maple syrup and a banana and child #2 plenty of butter and strawberries, I grabbed my laptop and decided to take refuge in the Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey.

I wanted to see how agricultural research funding looked relative to other fields and to consider what the place of agriculture in the research economy says about US higher education.

Research for the back forty.

If you’ve spent any time at an ag. college, one that is probably a land-grant university, you’ll know that the greenhouses and experimental fields are generally pretty far away from the administration building. People who know how to both operate a tractor and program in R are on campus, but you rarely encounter them because they are doing whatever they do on the farm, where the buildings are old and out of the way. But agriculture and related fields were probably the first research fields at the university and are arguably the foundation upon which the whole institution was built. So how much are we funding ag research today?

Let’s start by looking at all research expenditures by broad field. Federal funds account for a majority of research spending at colleges and universities, followed by state and local funding and institutional funds. Below is a graph of R&D spending by broad field since the 1970s. I’ve had expenditures constant in 2012 dollars so that we can see real changes in funding.

Look how much more is invested in life sciences research than in any other field. This is a broad category that includes agriculture but also biomedical research, and just about every biology-related field. As you can see below, life sciences have accounted for more than half of all research funding in higher education since the early 1970s (when data were first collected by the HERD survey). The share of all funding devoted to life sciences has gone up and down between 53% and 59% of total funding over the past 50 years. Drops in the share of total funding devoted to life sciences are driven mainly by the introduction of funding for additional areas of research to the survey. For example, HERD first records non-STEM federal research funds (education, business, law, etc.) in 2002, and we see a bit of a dip in the life sciences funding share between 2001 and 2002. But the overall trend is clear: the life sciences are slowly gaining on their majority share of funding.

From this view, we might think that agriculture funding is doing just fine. But that’s not really the case. While life sciences funding is increasing both in real terms and as a share of all funding for academic research, the sub-category of agricultural research has, as the NPR study argues, stagnated. Compare funding for agriculture with funding for biomedical research.

In 1973 US. higher education spent $1.1 billion 2012 dollars on ag. research and $2.2 billion on biomedical research. The sector spent $1 dollar on agriculture for every $2 on biomedical. But the gap consistently grew. By 2021, higher education spent more than $5 in biomedical research for every $1 on ag. research. Over the past 20 years, funding for ag. research has been more or less flat. All the while, biomedical research has seen an increase in investment from federal and other sources. From 2010 to 2021, total academic R&D expenditures increased by a third, but agricultural funding declined by 4.4% in real terms. The biggest decline of any major area of research. Budgets on the back forty are probably getting tight.

Ag school blues.

Higher education is a competitive enterprise, and nothing is more competitive than research. Research funding, for example, is one of the true zero-sum games in higher education. If I win the grant, you don’t. With stagnant funding, campuses that focus on agriculture may find it difficult to keep up.

The common saying that all money is green doesn’t really apply to higher education research. Federal money, especially federal research funding awarded by competitive grants, is among the most prestigious scientific money around. Competitive federal grants are hard to win, with NSF and NIH award rates consistently falling. These grants are awarded through a process of peer review, which signals quality and prestige. And they bring big overhead funding, sometimes up to 60% of the grant award. Ag money is less prestigious than money from say the NSF or NIH because it is often awarded in slightly different ways (less competitively) and because it is less associated with flashy science advances and publications in the most prestigious journals that get lots and lots of citations and recognition.

The status advantage of biomedical (and tech) research is widespread. A paper I coauthored Barrett Taylor and Nathan Johnson found that biomedical and technology research was associated with higher global ranking scores for universities at constant funding levels. In other words, a dollar invested in biomedical research was associated with a bigger boost to a university’s standing in the world rankings than a dollar invested in other areas of science, including agriculture. This status advantage is made plain in the US context. The prestigious Association of American Universities, or AAU, a club for the most research-active universities in North America, counts agriculture research as a “phase two” indicator. Funding from agencies like the NIH and NSF are phase one indicators. Research about food production is simply not especially prestigious. Ag. schools might be feeling blue rather than seeing green.

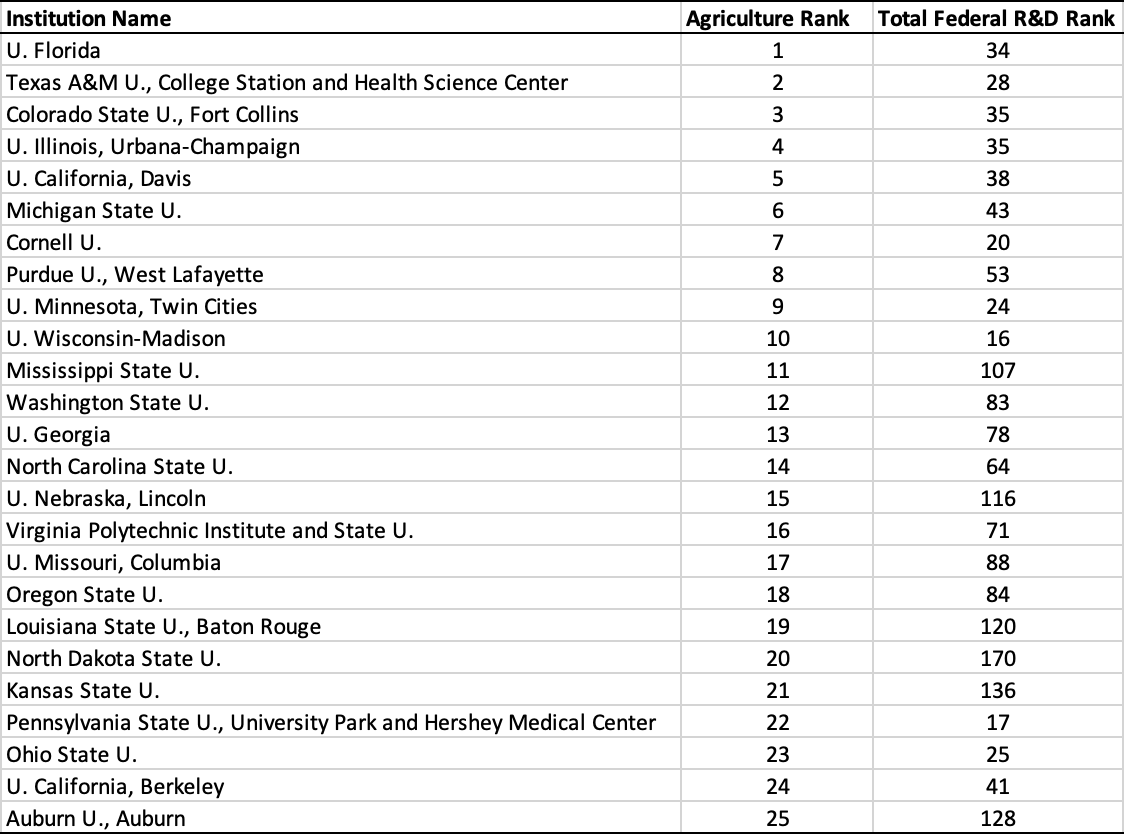

Below I show the top 25 federally funded agriculture research performers and also list their overall federal funding rank. Again these data come from HERD.

Leading agricultural research universities are overwhelmingly public institutions. Most are land grant universities. And while some, like Cornell and the Univesity of Wisconsin, are also among the top 25 overall federal research performances, most do considerably better on the ag. metric than overall. It is not that ag. schools are bad universities or anything like that. They are great places. But they do not carry the same kind of prestige associated with the list of top overall research performers, which includes places like Johns Hopkins, the University of Michigan, Columbia, Stanford, and Duke in the top 10. Generally speaking, the top 25 agricultural research campuses are less exclusionary, larger, and enroll more students from low-income families than the top 25 research performers overall (take my word for it). Ag colleges are, by and large, major research universities, but they don’t, again, generally speaking, have the status and resources of the top biomedical and technology-focused schools.

What is your point?

This is my point: The NPR story showed how stagnant agricultural funding was a problem because climate change and increased means that we need to focus on producing more food sustainably. This is undoubtedly true. The lack of sufficient ag. funding likely isn’t just an oversight. The NPR story suggests it is an irrational outcome of the byzantine federal legislative and appropriations processes. That’s probably a big part of it. But agricultural research is also low-status research. The most powerful universities and university groups might even see it as second-class research. It is not glam science. Probably relatively few universities and researchers are eager to do more of it. And those who are able and excited to spend more time in the corn fields are not the sort of people who have the most power or influence in US academic science. Generally speaking, ag researchers teach at less selective, lower-ranked, and less well-resourced universities. The status of lowly ag. research tells us about the status of applied - in the soil kind of applied - work that’s done mainly in Cow Colleges in the Midwest and the South and not so much in the Northeast and Midatlantic or in California. And that’s how it goes.

Ok, enough.

This was an interesting read, I learned (or re-learned?) some things. The status hierarchy as it relates to research deserves more study than it gets. Great post.