Brendan Cantwell

The US higher education world is very excited about predatory master’s degrees. The conversation started with a well-reported investigation but now master’s degrees are being called a scam. Almost on the wholesale. What should we make of that? I take a look at the place of master’s degrees in the US higher education landscape since 1980 and then think a bit about what the predatory master’s degrees mean and how we might think about the master’s degree in general. I’m not convinced the current conversation is productive.

Master of what?

I attend what could probably be classified as a cash cow master’s program. In 2003-04, I was a student at the University of Leeds (in that sunny town in the north of England) in a “taught” master’s program in the School of Politics and International Studies. The taught master’s included a thesis but did not the methods training in the “research” master’s degrees which were stepping-stones to the Ph.D. The majority of students in the taught program were international students, like me, paying a premium price. The story about how I ended up in Leeds is both long and personal, but sufficient to say I did not follow best practices when I made the decision. The decision was impulsive, and I took a private loan to pay for the program. The degree program itself was academically rewarding. The faculty was outstanding. I learned a lot about thinking and writing (I know what you are thinking, I didn’t learn enough). Things worked out fine for me. But that wasn’t a guarantee. It could have gone, as the Brits say, pear-shaped.

I recall my own experience because higher education Twitter is a state of excitement about cash cow master’s programs.

In early July, the Wall Street Journal published an incredible piece of reporting by Melissa Korn and Andrea Fuller on expensive master’s programs that leave students deep in debt with few prospects for professional success. Their report, which focused on selective private universities and programs in the arts and “helping fields” like social work, has kicked off a national conversation.

Recently, lots of ideas are circulating about how master’s programs are ripping students off. A Slate headline reads, “Master’s Degrees Are the Second Biggest Scam in Higher Education.” The Slate article is an interview of New America’s Kevin Carey by Jordan Weissmann. The interview is mostly about the sort of program reported by the WSJ but extends beyond that. Carey explained that Grad PLUS loans, introduced in 2006, opened the floodgates for master’s programs. Students could borrow for the total cost of attendance, providing an incentive for institutions to offer more master’s programs and jack up the price. The result, according to Carey, master’s programs have become such a scam, they are only behind fly-by-night certificates:

Probably the biggest scam in higher education remains one-year certificates offered by shady for-profit colleges that cost, like, $25,000 and don’t lead to a job. Master’s degrees are probably No. 2. Certainly, within the confines of colleges that are not legally for-profit, they are the biggest scam by far.

He goes on:

In some ways, they’re [certificates and master’s programs] more similar than they might seem. Many of them are one-year certificate programs. We don’t call them that. We call them master’s degrees, but that’s part of the problem. They are in fact often one-year job-oriented programs that are heavily debt-financed, marketed very aggressively through online web advertising.

The implication is that most master’s degrees are scam-y programs designed to fleece students. And that the market for master’s programs had boomed, primarily since 2006 with the implementation of Grad PLSU loans. Master’s degrees are debt-enabled moral rot.

The WSJ has created a tool to examine if graduate school pays.

These are big claims that will require extensive empirical study to suss out. I can’t do that here. Researchers probably started a bunch of new papers on master’s degrees after the WSJ article. So, we’ll see the results soon enough (if they go to pre-print, it will take years literally to get into journals). But I do want to take a peek at where master’s degrees fit into the overall picture in US higher education. I want to do this because it is easy. Also, it will give us a baseline understanding for further conversation and investigation into master’s programs.

The high-level picture

So, how many master’s degrees are there? Where do they fit in the landscape? I went to the Department of Education’s Digest of Education Statistics to find out.

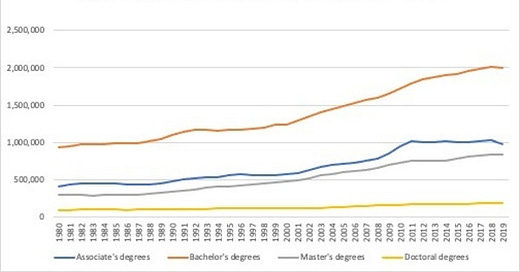

In 1980, US institutions awarded 302,637. By 2019, master’s awards rose to an estimated 832,000, a 175% increase. For sure, master’s degrees grew faster over the last 40 odd years. It grew at a greater rate than associate’s degrees (136%), bachelor’s (113%), and doctoral degrees (90%).

How about over more recent years? Between 2006 and 2019, master’s degree awards grew by 36%, associate’s by 35%, bachelor’s degrees by 31%, and doctoral degrees by 29%. Given that master’s degrees were growing from a smaller base than associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, it’s hard to say that master’s programs grew notably rather to other degree types after 2006 and the introduction of Grad PLSU loans.

All of the main degree types have grown over a long period, but master’s degrees grew faster. Not fast enough to change the order of degrees, which remained the same the entire period. In the 13 years before 2006, the number of master’s degrees awarded grew by 55%. The below line graph does not indicate any surge in degrees offered after 2006. If universities were pushing master’s degrees heavily after 2006 to cash in on loans, we would expect to see a jump in degrees in the years after. Maybe there was a little run-up in 2008 - 2010, but that is just as likely related to the recession (people go back to school during economic downtimes), and we saw a similar little blip in 2002 - 2004. You can’t see any sign of a master’s degree gold rush from these descriptive data.

What I don’t know is if prices for master’s degrees skyrocket. That would tell us something, especially if prices jumped a bunch after introducing the Grad PLUS loans. It might be that master’s tuition prices are growing no faster than other degree types, but that debt is going up faster because students are borrowing to pay for living costs using the PLUS loans. I don’t know. Maybe somebody does. If you do, let us all know.

Source: Digest of Educational Statistics, Table 318.10

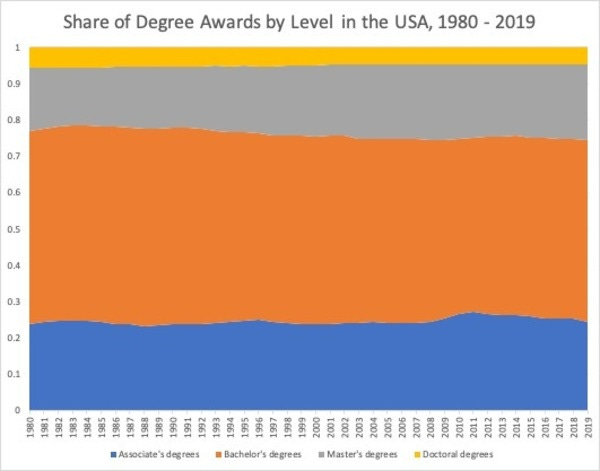

Let me kick this point one more time. Below is a figure showing degree wards by level as a share of all degrees awarded. In 1980, master’s degrees were 17.2% of all degrees. In 2019, master’s degrees were 20.8% of awards. So, it’s true, over nearly 40 years, master’s degrees became a somewhat bigger part of the overall degree portfolio. But master’s degrees first hit the 20% mark in 2003. So this has been a slow-building and graduate shift. Mostly what this figure shows is that the mix of degrees is remarkably the same as in 1980.

Source: Digest of Educational Statistics, Table 318.10, my calculations.

Who’s focusing on master’s degrees (and are they doing it for the money)?

Are master’s degrees concentrated in tuition-dependent institutions? Good question. I don’t answer it here. Ozan Jaquette asked a similar question in a 2019 Research in Higher Education paper. Jaquette looked at the relationship between state appropriations and master’s enrollment and degree production at public universities. He found that master’s degree enrollment and degree production grew with appropriations in the 1990s, perhaps because more state support allowed institutions to build more capacity. This association attenuated in the 2000s and essentially vanished. Jaquette does not find strong evidence that universities add master’s degrees enrollment goes up when appropriations go down. He doesn’t rule out the cash cow argument. A university could want more money whether or not state funding is cut or grows. But the paper doesn’t offer direct support for a cash cow argument either.

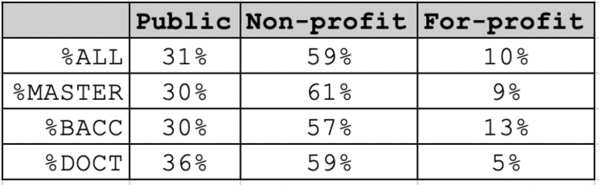

I took a look at master’s degree awards by control using cross-sectional data for 2017-2018. I removed associate degrees and looked a the share of degrees awarded by level by control. Not much of a high-level indication that privates are master’s heavy. These data don’t tell us much. The MA degree mix in each primary control type is more or less proportional to the overall degree share.

Digest of Education Statistics, 2019, table 318.60, my calculations.

What are the big master’s fields?

Three broad fields produce more than 100,000 master’s degrees per year. I used department of ed data again. First, we have business degrees (think MBA) at 197,089 in 2018-19. Second, we have education degrees, teachers and school administrations, and yes, students affairs and higher education, at 146,432. Health professions are also in 100,000-degree club (think nursing and public health) at 131,569. No one else is close. In 2018-2019 US institutions awarded 49,690 master’s degrees in engineering, 48,890 in public administration, and 45,667 in computer and information sciences. I think you get the point, right? My point is that the fields that offered lots of master’s degrees are very established, long-standing programs linked pretty closely to specific occupations. Together, these six broad fields account for about 75% of all master’s degrees awarded in recent years.

Let’s see how these programs do in terms of providing earnings relative to debt. Student loan advance givers often say that the debt accrued from a degree should not exceed your salary the first year after you graduate. The Wall Street Journal has created a tool using federal College Scorecard data to show the value of programs based on this debt-to-earnings metric. Take a look for yourself. Here is what I discovered about the programs I looked at:

Of the computer since and engineering categories in the WSJ, only two programs, two, appear to exceed the debt-to-salary rate.

Public administration is a bit of a different picture where about 25 programs exceed the threshold, and many more are right around the threshold, but the majority of programs are well behind it.

Of the hundreds of nursing master’s degree programs, the biggest category in health, six exceed the threshold. Go to nursing school. Do good and pay your debt.

For both teacher education and educational administration, most programs are on the right side of the debt-to-income ratio.

There are even more business administration master’s programs than there are nursing programs. Business is prime potential for scammer programs. But only 11 of the hundreds of programs exceed the value threshold.

A few more observations.

Check out the business administration programs versus the fine arts programs, which the WSJ article spotlighted.

You’ll notice that there are WAY more business programs than arts programs. You’ll notice that most art programs don’t meet the threshold requirement; many blow past it. Wow. Yet, the vast majority of business programs do pretty well on the debt-to-income ratio.

Where's the scam?

Of course, there are predatory master’s programs. The programs featured in the WSJ story do seem bad. They are taking advantage of students by exploiting their aspirations. It’s a prime example of how aspiration and inequality are explored by institutions, as Tressie McMillan Cottom described in LowerEd. It might not be unfair to call these programs scams. But we probably want to be careful about defining any program that exceeds the debt-to-income ratio of 1 as a scam.

When I was playing around with the WSJ tool, I think I noticed something. Many of the institutions whose programs fell beyond the threshold fell into three catalogs. My categories are anecdotal, based on my subjective observations. And it’s not a complete accounting of every program. So take it for what it’s worth (you can be the judge of that).

For-profit colleges: Not a big surprise. There is lot of evidence about how for-profits have high costs and don’t provide a great return to students regarding post-graduation earnings.

Highly selective privates in desirable cities: Here’s looking at you USC, Columbia, NYU. These programs, especially in arts and helping fields, irritate the public and reform. And justifiably so. These places charge extraordinarily high prices for programs in areas where the pay is low or the outcomes are uncertain. The students want to live in a good city. They want the halo of a degree from a prestigious institution. These places are trafficking in desperation and desire. They are laundering LowerEd through Gothic spires. Of course, not all their master’s programs are doing that. But some of them are. That’s the thing.

HBCUs and other under-supported universities that support marginalized students: Of the ten business administration programs that exceed the threshold, 3 are public HBCUs. Friends, 30% of MBA programs are not found at HBCUs. Not even close. The prominence of HBCUs points to something other than a scam perpetrated by the institutions. Public HBCUs have been chronically underfunded for 150 years. Black people are discriminated against in the labor market. The racial wealth gap means that Black people often have to borrow to get an education. What we see here could be a structural problem. One that you can’t fix by regulating scams.

Credentialism is an issue.

But it might not be a scam. The need to get an MBA to advance in business is possibly not justified by what students learn in MBA programs. It might be about social capital - the networking that happens in MBA programs. It might be about signaling. Education credentials could be about school district mandates or salary schedules, which might not result in better teaching. These debates are old, and they are legitimate. We should try to understand how credentialism distorts education and labor makers. But this is not a new scam.

What should we do?

I don’t know. Would you please not ask me? There are several policy fixes to address predatory master’s degrees. Grad PLUS could be capped or eliminated. Gainful employment regulations that make federal loan availability contingent upon a good debt-to-income ratio could be imposed on all sorts of master’s programs (including at non-profit and public institutions). Or some risk-sharing arrangement could be imposed where the school has to pay back part of the loan if a student defaults. I’ll leave that to the real wonks.

In addition to the technocratic solutions, however, I think we need to keep things in perspective. Master’s degrees are a long-standing part of US higher education. Most master’s degrees are in very well-established fields that have been around for a long time. In most programs, most students who borrow do just fine, and have a good income relative to their debt. Graduate debt might be a problem, but dragging all master’s programs seems an unnecessary response.

Probably the root causes of credentialism and the exploitation of aspiration and desperation are things we should be worried about. But saying “master’s degrees are the problem, let’s regulate them out of existence” isn’t really a solution to those problems.

Maybe my reasonable personal expense is a cash cow master’s program clouds my judgment. But let us slow down before we declare master’s degrees the second biggest scam in higher education.

Ok enough.

Edited on July 20 to correct a spelling error.